Deep underground in one of Vancouver’s most renowned hotels bustles an army of employees serving the guests who stay for a meal, stay for a night — and each other

Denise Ryan

Sun

Behind the scenes of the Fairmont Vancouver Hotel, in-room dining server Cheryl Labrecque heads off with a meal to a guest’s room. Photograph by : Ian Smith, Vancouver Sun

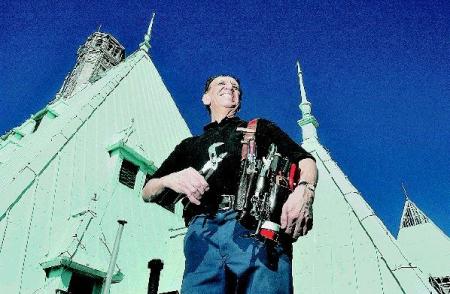

Carlos Sander, a 37-year employee with the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver, stands on the roof of the hotel. As a maintenance engineer, he has to change the light bulbs that shine on the copper roof, replace air filters and other tasks needed to keep the hotel functioning. Photograph by : Stuart Davis, Vancouver Sun

Enter the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver, walk its luxurious carpeted hallways and you’ll get what you pay for — a deluxe stay in the style of what’s called, in the industry, “grand hotel.”

It’s probably as close as any of us will ever get to experiencing how the other half lives.

Polished surfaces. Triple-sheeted beds. Staff.

“Housekeepers” (they used to be called chambermaids) in black uniforms with crisp white aprons that discretely fold your discarded clothes, replace your towels and fluff your pillows.

Dinners that magically appear in your room on trolleys draped in white linen and served on plates covered in silver domes.

Every need and want discretely serviced.

But nothing is ever quite as it seems. Along with the famed ghost, the “lady in red” who is said to haunt a certain elevator, the hotel has its secrets.

In the elevator, you won’t run into a room service trolley or the huge carts that haul the sweaty bed linens, old newspapers and candy wrappers away from your room.

You won’t see the houseman delivering a baby’s crib to the suite where new parents have just checked in.

Staff come and go almost as invisibly as the ghostly lady in red.

Call it upstairs/downstairs, or front end/back end, there are two halves to this old-style hotel, and what you don’t see is, in some ways, more interesting that what you do.

Inside the hotel is another world — a maze of hidden hallways, rooms and elevators that is part command centre, part community centre. It’s a place employees call “the inner city.”

The inner city dips three levels below Burrard Street, houses, clothes and feeds up to 450 employees daily, and comes complete with its own private elevators, offices, change rooms, showers, lounges, kitchens — even a restaurant.

It is here, behind the scenes that the hotel really lives.

Its interior corridors hum with staff, and private service elevators lead to hidden doors that open discretely to the quiet halls of each floor.

The Fairmont Hotel Vancouver’s remarkable exterior face has been a fixture in the city since its completion in 1932 — a green roof made of oxidized copper, and carvings of griffins, flying horses and gargoyles adorn its walls. It was, until 1972, Vancouver‘s tallest building.

And, like its facade, the hotel’s massive city-within-a-hotel design is something — mostly due to the premium cost of space — newer hotels simply don’t have.

A full 35,100 square metres (390,000 sq. feet) are set aside for staff operations.

The hidden community

The way into this world is through a separate entrance close to the breezeway where the valets take guest car keys and usher them into the hotel’s “upstairs.”

At the bottom of the steps that lead to the “downstairs,” a huge billboard displays snapshots staff have taken of themselves celebrating holidays, birthdays and anniversaries.

In this subterranean world, the hallways are worn from the traffic of hundreds of feet. There is no plush carpeting. But there is something just as welcoming — a display of flags representing the 25-plus countries from which the staff hail.

Like domestic “downstairs” staff at an old manor, most of the workers, many of whom are immigrants, are more or less invisible. Guests only experience the comforts they provide. But in the colourful world behind the scenes, everyone has a role and no one is invisible.

Handpainted on the wall above the staff doorway is a sign that reads Through these doors the nicest people pass.

The day staff arrive each morning in two waves, one at 6 a.m., another at 11 a.m. For everyone on shift, the first stop is the uniform room.

Quyen Chaw, affectionately known as “Queenie,” presides over the large shop stocked with sewing machines, industrial presses and laundry.

Taped to the countertop is a friendly note asking staff to please not jump over the counter to grab their uniforms.

Rolling racks of crisp black dresses, white aprons, chef’s jackets, waiter’s black-and-whites and manager’s suits wait to be claimed, fitted or pressed.

In any given day Queenie, who immigrated from Saigon 20 years ago, will sew up a hem on a manager’s skirt, fix a stray button, even do a quick repair for a hotel client.

Queenie’s whole career has been conducted here, below ground and behind the scenes; she services those who service the guests, and she’s happy to do it.

“The people here are like family,” she says, her face splitting into a huge grin. “Better than my real family.”

That may be why, even after retirement, many employees return regularly to dine in the hidden interior restaurant, The Chattery, which is reserved just for staff.

The Chattery, run by its own full-time staff, serves up breakfast, snacks, coffee, hot and cold lunches, and dinners daily. At the Chattery, housekeepers, doormen, housemen, supervisors and managers break bread together.

There are monthly lunches themed to the staff’s different nationalities.

When there’s been a particularly good banquet upstairs, unfinished delicacies are brought down for staff.

Younger members of the 425-strong daily team chill out on leather sofas in a lounge beside the Chattery with a plasma TV and a couple of wired up computers for checking e-mail and surfing the Net.

There is even an internal daily newspaper listing events, VIP guests, weather, staff birthdays.

On the walls of the long hallways that snake maze-like through the subterranean city, a series of bright murals depict employees in all their aspects.

The murals were created by Peter Teo, who worked in the kitchen as a cook for 20 years, retired in 2005 and returned in 2006 to paint the walls.

Smiling broadly in the mural is executive chef Robert Le Crom.

Le Crom, who comes from France, is proud of all the kitchens he runs at the hotel — three main kitchens, plus prep areas — but the pastry kitchen where racks of cinnamon buns cool and a machine churns melted Callebout chocolate for the hand-dipped chocolates, is his pride and joy.

“Pastries are expensive to produce,” he explains, and his hotel is one of the only ones in the city that doesn’t outsource its cakes, croissants and chocolate.

“When you go outside, it all tastes the same, it’s mass production,” says Le Crom.

“Not only do we do it all ourselves, we do volume. Sometimes for a banquet, we do 800 creme brulee. It takes two people all afternoon to blowtorch the sugar on them.”

Le Crom sticks his finger in a chocolate mousse that’s been set aside for him.

“I taste everything. You’ve got to love food,” he says.

Like the rest of the staff, you won’t see Le Crom when you stay here.

Le Crom gestures around the huge kitchen where a chef cracks fresh lobster claws. “You won’t find a back-of-the-house like this one anywhere in the city. Space is too costly now. Staff have barely anywhere to move in the newer hotels.”

Le Crom oversees the 2,500 meals that are served in the hotel each day — he needs the space.

From the downstairs hallways, a private bank of elevators runs the staff up to each floor.

Each staff lift bears a nameplate over the door, and two are named for former staff members.

Louie’s Express is named after Louie Barillaro, a room service captain who started with the hotel in 1947, and retired in 1992.

Over his 45 years, Barillaro delivered 30 room service orders a day, five days a week. He died in 2006.

The Lady Frances is named for Frances Katrina Kay, the licensed operator of the elevator for 32 years, back when it was a manual system.

During her time as the elevator operator, Kay made at least 118,800 trips up and down her elevator car.

These staff elevators truck up the housekeepers and housemen, the room service attendants and the banquet waiters, letting them off at the hidden passageways that connect to the main hallways on each floor.

Irma Bazan, the assistant housekeeper, has worked at the hotel for 19 years, and hails from Peru. Bazan rides the elevators and walks the hidden corridors every day as she supervises all 40 room attendants, ensuring each room is spotless.

It’s one of the hardest jobs in the hotel, and one in which workers are more prone to injury. A 2006 study commissioned by the University of California at San Francisco showed that 75 per cent of hotel room keepers experience work-related pain.

Repetitive stress injuries are an issue for all hotel workers, says Laura Moyes, organizing director for Unite Here, Local 40, which represents 5,000 hotel workers, though not the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver’s employees.

“Higher thread-count sheets can add a pound per sheet; multiply that by three sheets per bed and 15 rooms per shift,” says Moyes. “There are more injuries to hotel workers than coal miners.”

Moyes says that muscular-skeletal disorders are common, and “housekeepers knees” can leave workers with permanent, painful blackspots on their knees.

Strength in numbers

Janice Yuen has been turning down bedsheets as a housekeeper for nine years since coming to Vancouver from Hong Kong.

“It’s a good job,” she says, “but not an easy one. I lost 20 pounds my first six months.”

Burnout is a problem among housekeepers, who truck trolleys laden with fresh towels, linens, toilet paper and cleaning supplies down the down the hallways.

Three times per shift a strong-armed houseman empties the linens from their trolleys, but even so, it’s a hard job, made easier by the occasional dollar bill slipped under a pillow by a customer.

Tips are less than they used to be, at least among Americans since 9/11, but for Yuen, it’s not all about tips.

“When I finish the room nicely, I feel very satisfied,” she says.

In banquets, it’s not unusual to find servers like Helen Cranage setting up to 1,000 tables for a dinner. After 17 years, prepping for and serving a dinner for hundreds or thousands doesn’t faze her.

“I’ve served Bryan Adams, Diana Krall and her family, Bill Clinton.”

She blushes at Clinton‘s name.

“He was very, very charming, very charismatic,” she says.

Serving celebs is one of the perks, says Cranage, who never expected she’d stay so long with the hotel.

But there there seems to be something that keeps the “downstairs” staff of this hotel coming back to work year after year. It may be the ultimate irony that in a hotel, where the visitors upstairs are transitory, the staff is enduring.

The answer could well lie within the walls of the “inner city,” a secret of our city, a place where whole lives are conducted, while upstairs, the guests come and go and eat and sleep, blissfully unaware.

– – –

FAIRMONT HOTEL VANCOUVER BY THE NUMBERS

Hotel’s stars: 4

How many royals have stayed here: 15

Times the Queen has dined at the hotel: 3

Chefs/cooks on shift each day: 40

Meals served each day: 2,500

Meals served in the Chattery each day: 475

Dishes washed in a day: 7,000

Scones baked in a day: 20 dozen

Light bulbs changed in a week: 154

Staff uniformed by Queenie per day: 300

Bed sheets used in a day: 3,500

Longest serving employee: John Giannis, chef de partie, on staff since 1969.

Cumulative years of service hotel staff has at present time: 5,807

© The Vancouver Sun 2007